How Antique Linen was Made

All of my linen is between 50 and 130 years old and made from flax and hemp, which were grown by the same European farmers that hand-wove the material. The women weavers of former times spent their evenings weaving this amazing linen, often working only by candlelight. A weaver would work four to six hours to produce just 60 centimeters (24 inches) of this linen. The finished linen was used to make clothing and bedding as well as grain-sacks and wagon planes.

Today, linen of this quality and kind is no longer grown by European farmers. Like the rest of us, they buy their clothing ready made, and the conveniences of man-made materials render the need for this kind of linen obsolete. More importantly, to grow and hand produce linen is no longer cost-effective. Flax that is now grown in the vast fields of northern Europe is used to produce the more economically valuable linseed oil.

Today, linen of this quality and kind is no longer grown by European farmers. Like the rest of us, they buy their clothing ready made, and the conveniences of man-made materials render the need for this kind of linen obsolete. More importantly, to grow and hand produce linen is no longer cost-effective. Flax that is now grown in the vast fields of northern Europe is used to produce the more economically valuable linseed oil.

Old linen bolts are becoming harder and harder to find. In a decade or so, most of the old farmers' linen presses and their daughters' dowry chests will have yielded up their historic treasures to be loved by others, who will appreciate their handmade linen for its artistic beauty.

From Flax to Linen

German folklore is replete with images associated with flax and its production processes. Ancient stories, such as Sleeping Beauty (think of the spinning wheel) and Rumplestiltskin (the King’s demand that the miller’s daughter spin straw into gold) tell of the important role that flax and the tools used to turn it into linen played in the lives of the European people.

German folklore is replete with images associated with flax and its production processes. Ancient stories, such as Sleeping Beauty (think of the spinning wheel) and Rumplestiltskin (the King’s demand that the miller’s daughter spin straw into gold) tell of the important role that flax and the tools used to turn it into linen played in the lives of the European people.

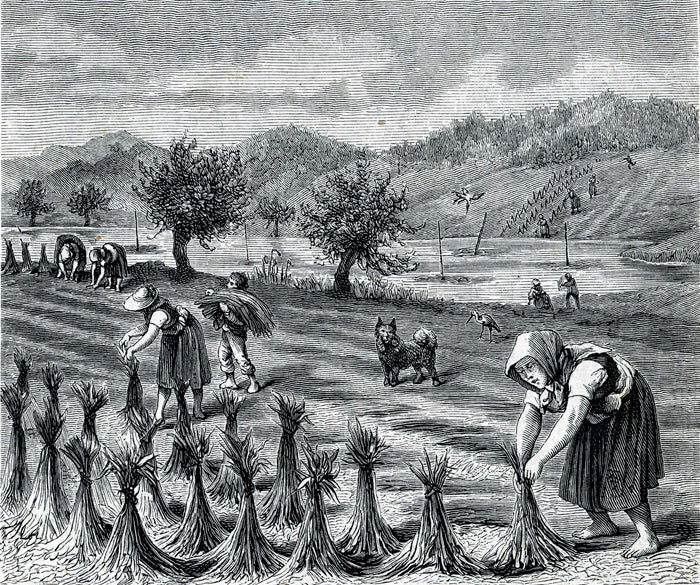

For the farm families of yesteryear, linen was needed to provide clothing and bedding as well as grain sacks and other items necessary for farm work. Most of the backbreaking work in making linen was performed by women, as portrayed in the pictures below, taken from a German Almanac published in 1882.

Step 1 - Pulling

Flax was sown in March or April. It was a fast growing plant that grew about 40 inches tall. Sometime during August, when the plants’ color turned to a golden hue, the plants were ready for harvest. In order to produce the best quality linen possible, the fiber had to be hand harvested by either pulling the whole plant by the root or by cutting the stalks very close to the ground.

Step 2 - Separating

After the harvest, flax seeds were removed through a process called “rippling”. During this process the plant stalks were pulled through a rippling comb, which was an iron or wooden device that was studded with nails for the easy removal of seeds and other undesirable plant elements.

Step 3 - Retting

To dissolve the pectin, which binds the plant fibers together, the remaining flax stalks had to be rotted or “retted”. This could be achieved periodically, to allow the dew to accomplish the rotting process. A faster way to decompose the pectin was to submerge the stalks deep into the local pond and weigh them down with heavy objects, such as stones or logs. With this method, the retting took just a few days.

Step 4 - Drying

In late August or early September, after the plants were retted and retrieved, the farmers tied them into small bundles and laid them out in the open fields to dry. This was done to bring the rotting process of the fibers to an end. Retting the flax stalks too long would render them brittle and unsuitable for textile production.

Step 5 - Roasting

When the weather was damp, it was often necessary to roast the flax in special ovens at very low temperatures until it was dry.

Step 6 - Breaking

After drying, the flax was ready for “scutching”, also called the “swinging” process. Small bundles of stalks were dragged in a swinging motion across a nail-spiked board to remove the woody parts of the fibers. At this time, only the long, soft flax strands remained, which were twisted into braids, ready to be spun. When the work was done, the young people of the village would meet for an evening of play and dance, the so-called “swing dances”.